How Biology Inspired Computer Vision and CNNs

How the brilliance of the human eye inspired the development of convolutional neural networks and paved way for machines to see.

For centuries, the human eye has been a source of fascination for scientists and philosophers alike. Its ability to process and interpret the world is a feat of biological engineering that has long been a source of inspiration for artificial intelligence (AI). From the dynamic range of light it can handle to the intricate neural networks that process visual stimuli and produce our perceptions, the eye (and visual cortex) are marvels of efficiency and complexity1. One of the most compelling examples of this inspiration in AI is the development of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a powerful and popular artificial intelligence model used in computer vision, facial recognition as well as image classification, and even genomic sequence-related tasks, among many others.

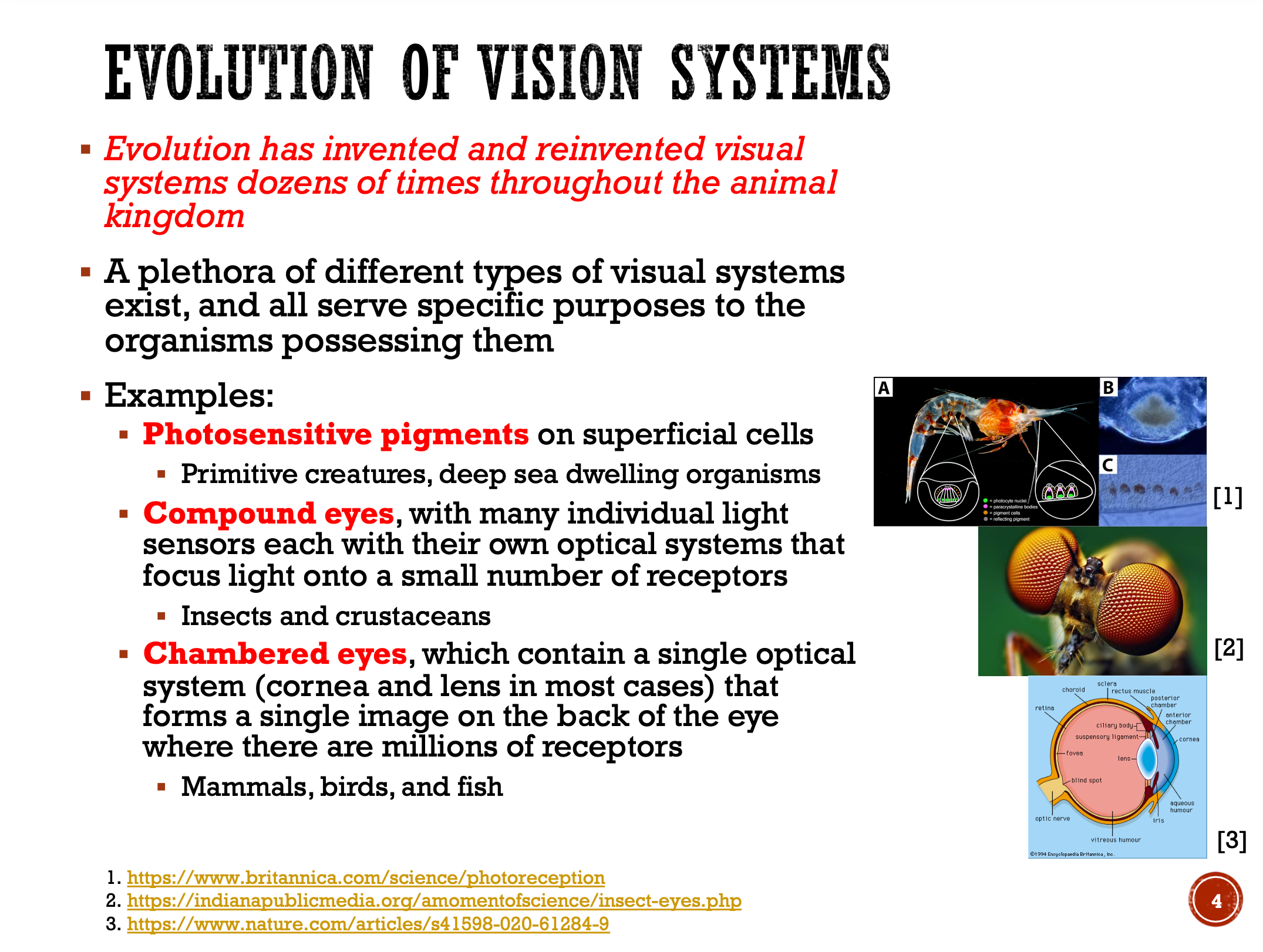

Yan LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and colleagues first pioneered early CNN models in the 1980s and 1990s, with a particularly notable one known as LeNet. Interestingly, CNNs predated the deep learning revolution that occurred in the 2010s, which was motivated by an increase in processing power that allowed us to finally fully leverage multi-layer neural networks with gradient descent algorithms (i.e., backpropagation). CNNs thus serve as one noteworthy example of how AI can be inspired by biological systems. Why try to reinvent the wheel when biology has spent millions of years refining and testing its biological systems? Lifeforms have the most sophisticated machinery known to mankind. AI engineers know it is wise to lean on life for inspiration!

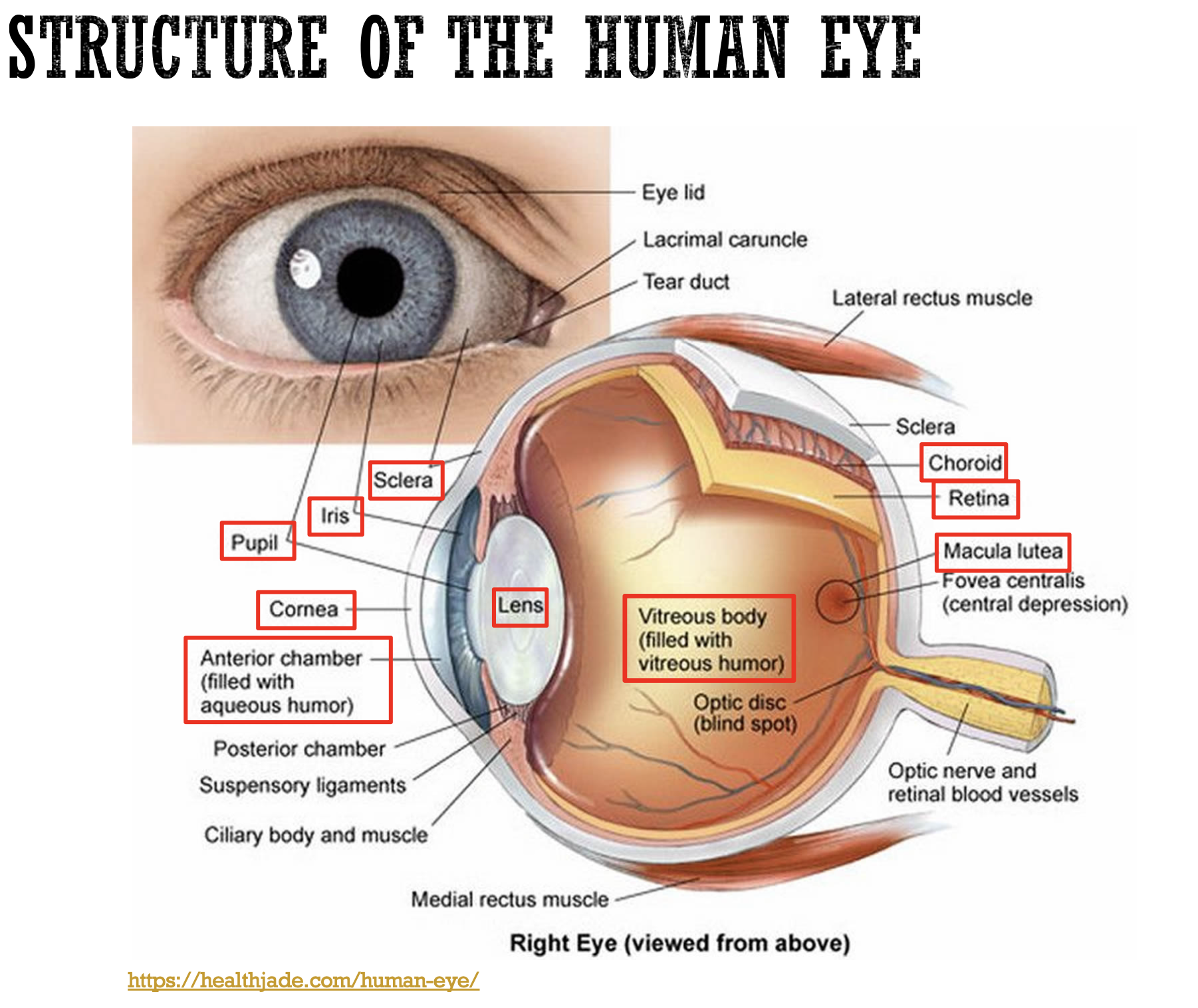

The Eye as a Biological Camera

The human visual system is a three-part marvel consisting of the eyes, visual pathways, and the visual centers of the brain. The eye's primary function is to capture light and convert it into neural signals. It performs this detection and signal processing and decoding across a wide, dynamic range of light levels that can differ by factors of over 100 million (a challenge that is nearly insurmountable for optical and video devices).

At the back of the eye lies the retina, a thin, fragile meshwork no thicker than a postage stamp. The retina contains photoreceptors (rods for light detection and cones for color) that detect light and convert it into electrical signals. Rods are highly sensitive and can respond to even a single photon of light, making them essential for vision in dim light, while cones are responsible for color perception and fine spatial resolution in bright light. Humans have three different cone cell types that interpret different wavelengths of light spanning the red, green, and blue wavelength ranges. When all are working appropriately, we have normal color vision, although a decently large percentage of the population (particularly male population where ~8% or 1 in 12 men) have a form of color deficiency or blindness which makes it difficult for them to distinguish between certain colors. One good tip is to avoid using red and green as opposing colors on presentations and posters, as a sizable percent of those with color deficiency have trouble differentiating between the two.

Another interesting fact about the visual system is that it has a "duplex solution/theory" to the tradeoff between sensitivity and resolution, with rods providing scotopic vision (low-light sensitivity) and cones providing photopic vision (high-resolution vision in bright light). This is why when you have low light conditions, such as when you are stumbling around in the dark to go to the restroom at night, what you see is mostly dark gray as opposed to the vibrant colors you see during the daytime when you have more light, because your rods can detect the small amount of light that is there to allow you to make out shapes of large objects around you, but your cones require more light to operate successfully and allow you to experience color vision.

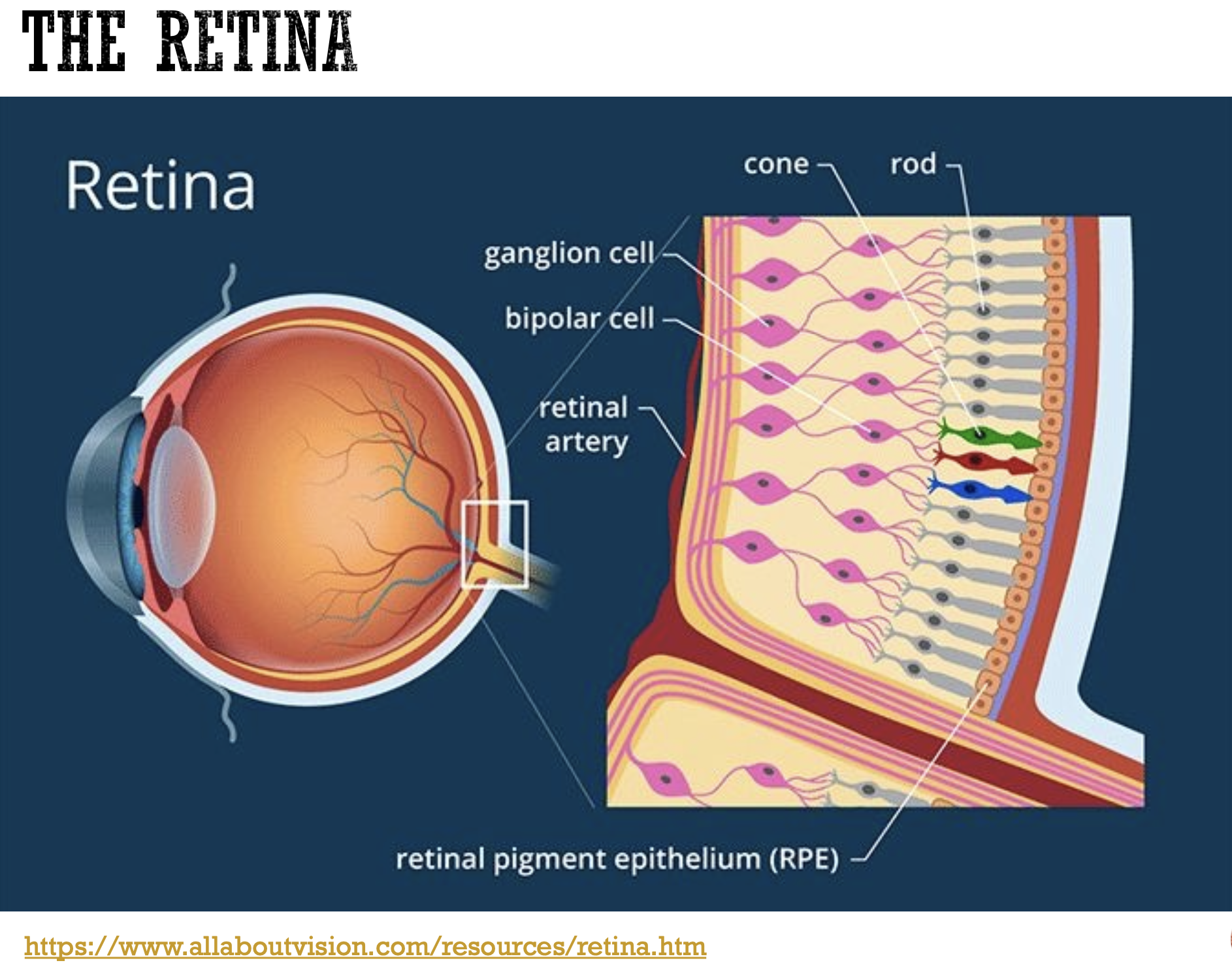

The Retina's Neural Architecture: A Blueprint for AI

While each photoreceptor gauges the amount of light falling on it, vision is far more complex than just millions of points of light. The retina's genius lies in its neural architecture, which transforms these raw measurements into meaningful visual information about edges, contrast, and features.

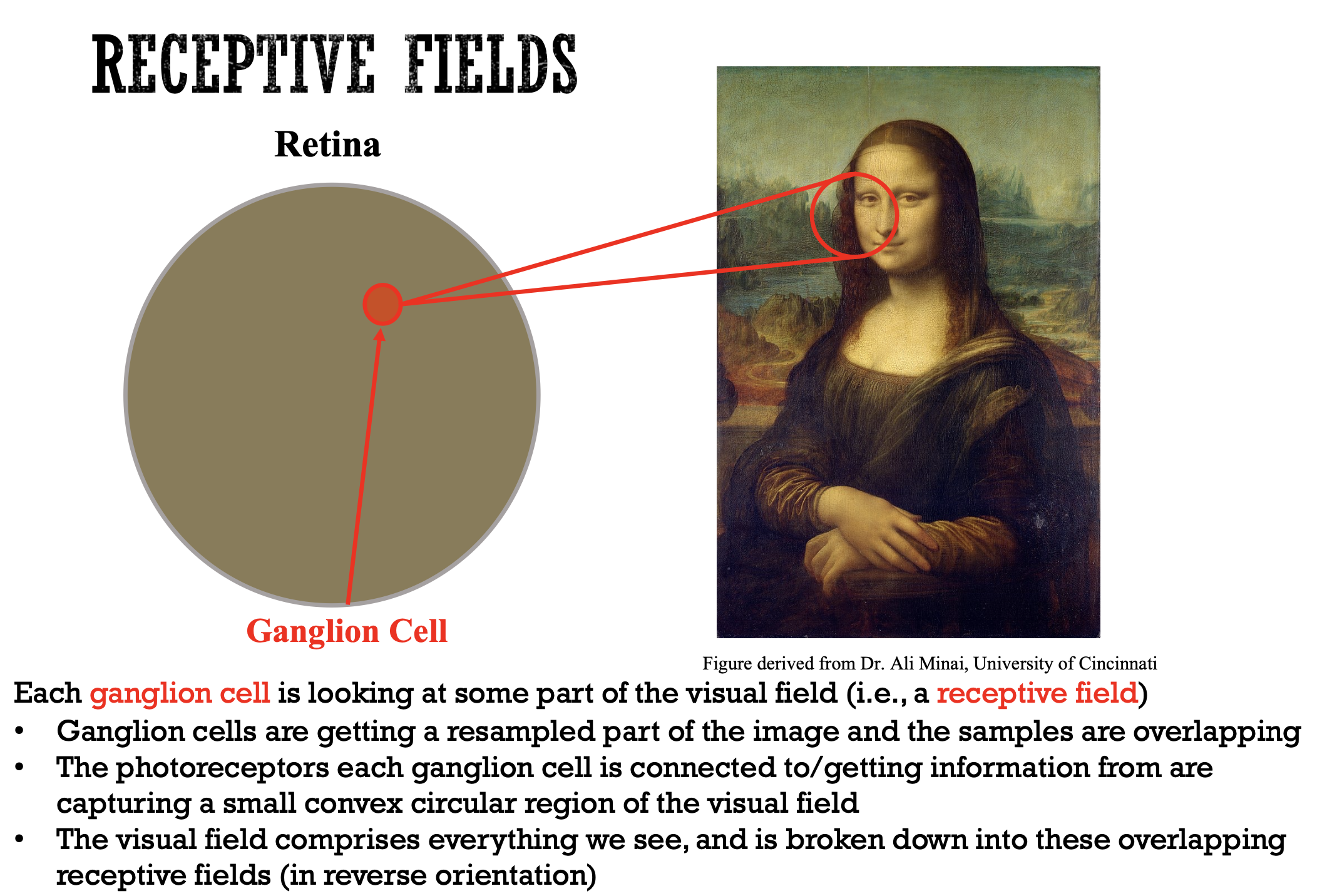

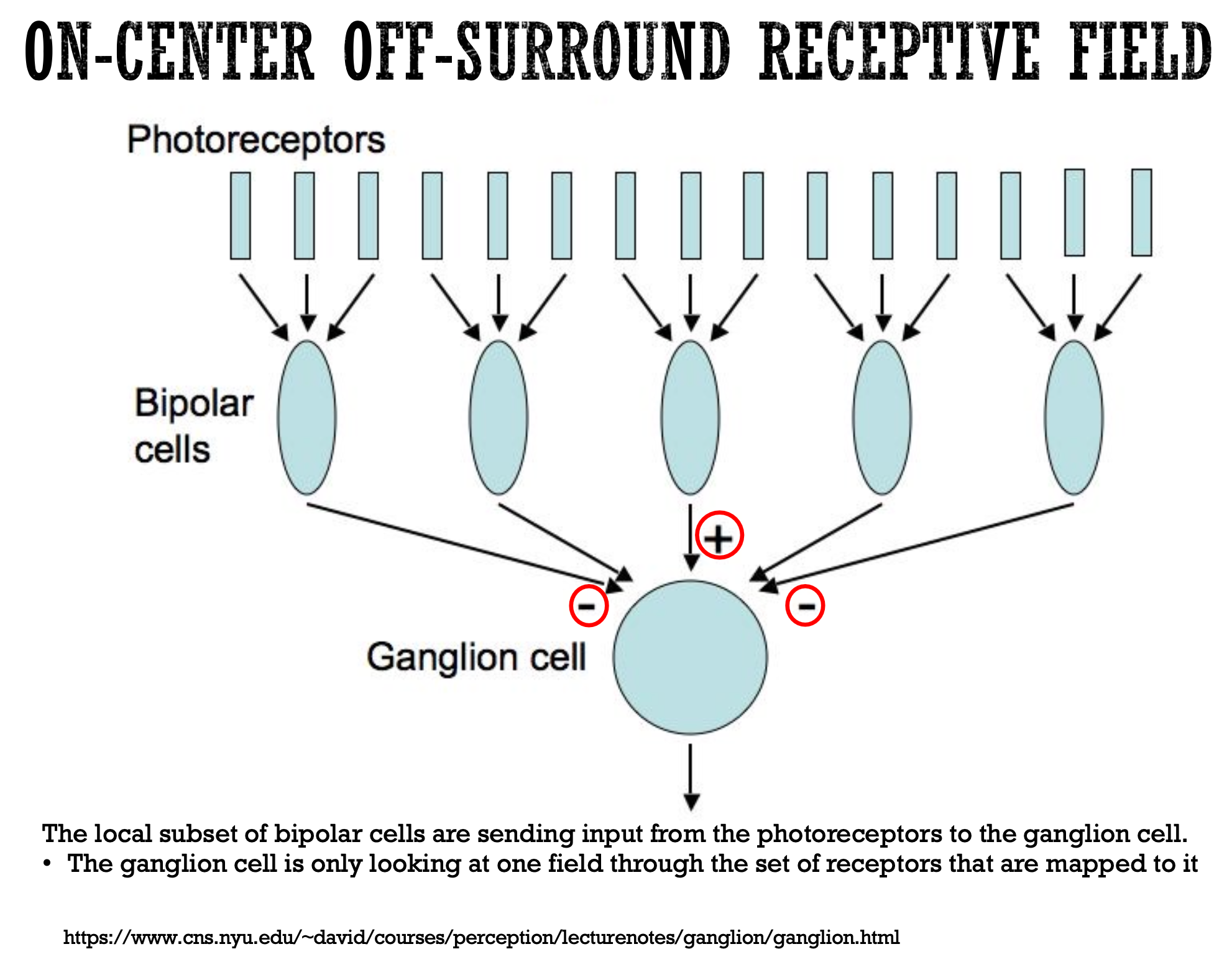

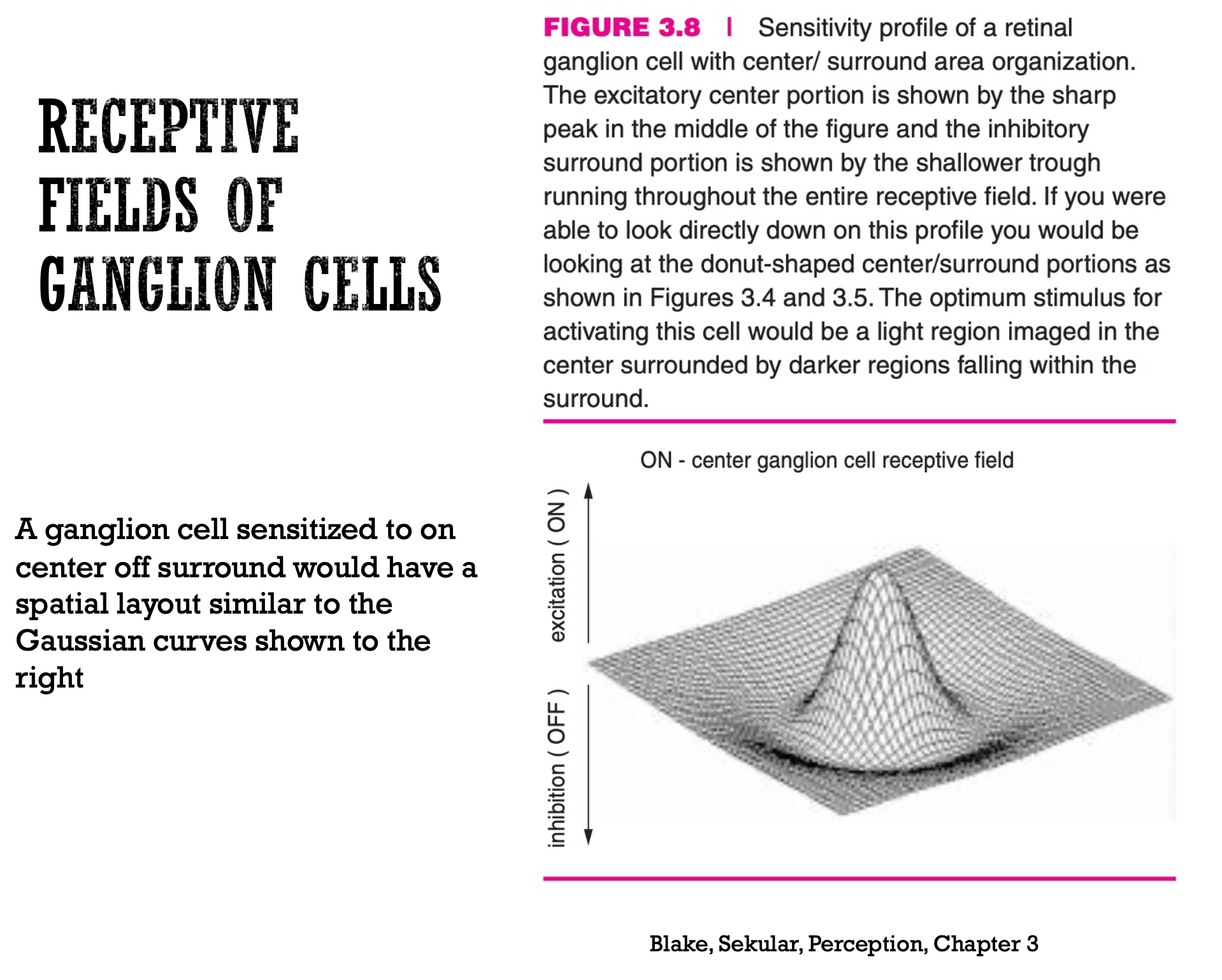

The neurons responsible for the final stage of processing within the eye are the retinal ganglion cells. These cells have a receptive field, which is the specific patch of the retina that responds to stimulation. These receptive fields are organized into "ON" and "OFF" regions, which are antagonistic to each other. An "ON" region responds to an increase in light, while an "OFF" region responds to a decrease. Certain decoding schemes in the brain make sense of the ON and OFF stimulated regions to decode what is happening in the visual field and to make sense of what is being seen.

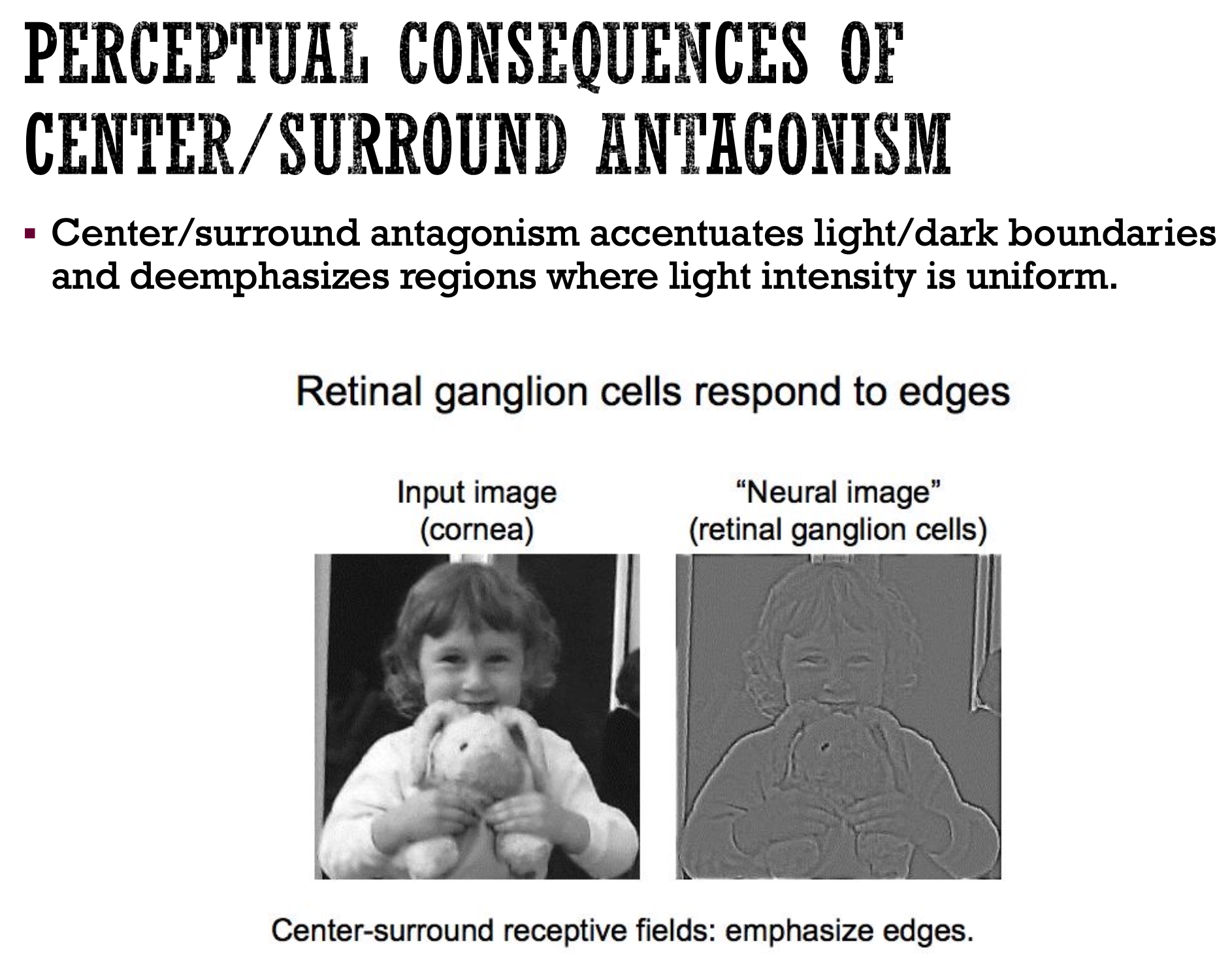

This center-surround antagonism is a critical feature that allows retinal ganglion cells to respond most strongly to edges and boundaries rather than uniform surfaces. This process, known as lateral inhibition, accentuates the contrast between light and dark areas, which is a fundamental step in recognizing shapes and objects. The "neural image" created by the retinal ganglion cells emphasizes edges, providing a more processed representation of the visual world than the raw input image received by the cornea. This process is leveraged in convolutional neural networks, where we use "filters" or weighted matrices with different starting values to preferentially weight or focus on different regions in an image to create greater contrast or intensities along edges or specific features (think changing the filter on the images you have taken on your phone to increase contrast or sharpen edges, for instance). Keep reading to learn more about CNNs.

From the Retina to the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

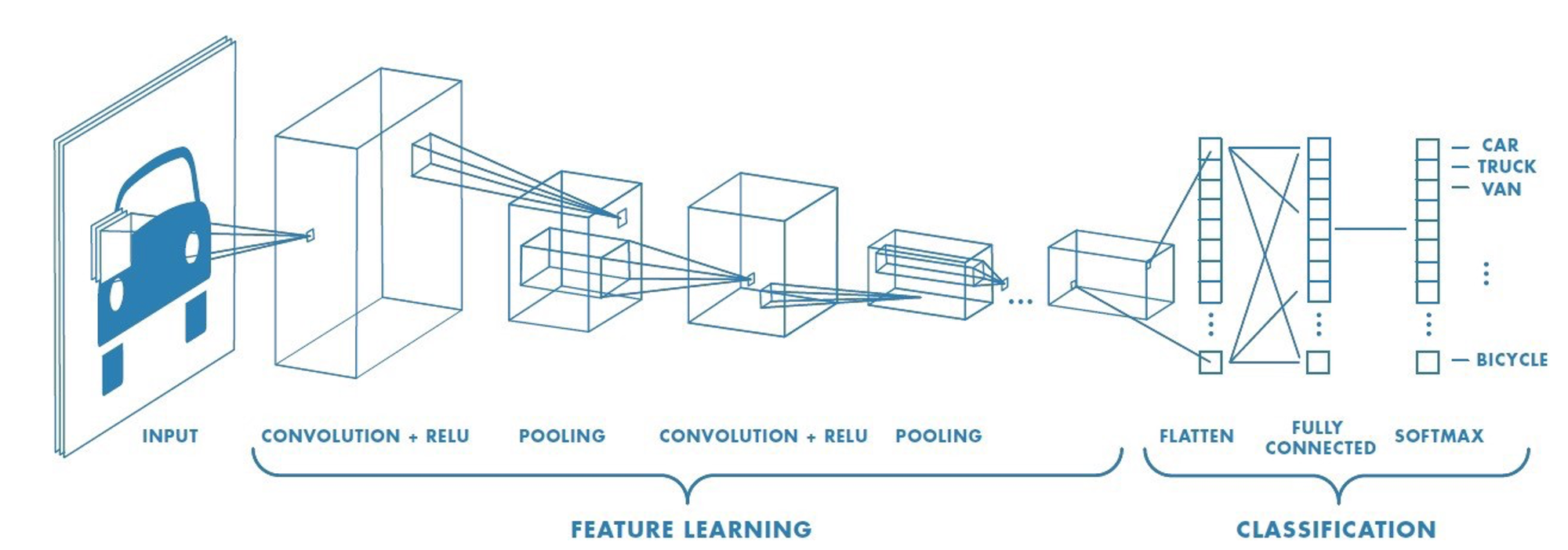

The structure and function of the retina's receptive fields served as the direct inspiration for the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Like the retina of the eye, the CNN is a type of artificial neural network designed to process data with a grid-like topology, such as that in videos and images.

The core of a CNN is the convolutional layers, which mimic the receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells. These layers use small, learnable filters (or kernels) that "slide" over the input image and transform the weights of the image matrices into different variations of the initial image. Each filter is designed to detect a specific feature, such as a horizontal edge, a vertical edge, or a curve, for example, in a small region of the image. This is analogous to how a ganglion cell's receptive field detects changes in light intensity to identify an edge. By applying these filters across the entire image, the network creates a feature map that highlights where these specific features are present, and this information can be later used during classification tasks once the important regions are identified within an image.

Just as the retina's neural network processes raw light signals into a more refined representation of edges and forms, a CNN's layers progressively extract more complex features. The initial layers might detect simple edges, while deeper layers combine these simple features to recognize more complex patterns, like textures, shapes, and eventually, entire objects. The network learns the best filters for a given task by being trained on vast datasets of images, automatically discovering the most salient features for object recognition during the learning process.

The architecture of a CNN, with its alternating layers of convolution, pooling, and classification, mirrors the hierarchical processing of the human visual system, from the photoreceptors and ganglion cells in the retina to the higher-level visual centers in the brain. It is exciting to dream about what other exciting technologies have yet to be inspired by current biological life forms.

Conclusion

The next time you snap a photo with your smartphone or see a self-driving car navigating city streets, remember the intricate biological system that made it all possible. The human eye, with its dynamic range and elegant processing, provided the foundational blueprint for some of the most transformative technologies of our time. By way of studying the simple yet profound principle of center-surround antagonism and visual stimuli detection and interpretation schemes in biological life forms, we were able to create an AI model that could "see" the world in a fundamentally similar way, proving once again that some of the most revolutionary ideas are inspired by nature's own genius.